The Peasants’ War and its consequences

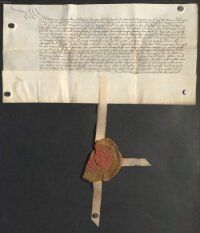

In the spring of 1525, the Peasants’ War reached the territory of the Mainzer Oberstift. The town of Aschaffenburg initially took a negative stance towards the "uprising of the common man". The St. Peter und Alexander collegiate church also supported the archdiocese of Mainz with monetary contributions to raise troops, as evidenced in a document dated 15 March by Wilhelm III von Hohnstein (c. 1470-1541), bishop of Strasbourg (from 1506) and governor in the stead of the absent archbishop of Mainz, Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545, archbishop from 1514).

The situation changed, however, when the town of Tauberbischofsheim, which, like Aschaffenburg, was a member of the "Neunstädtebund", broke away from the alliance and joined the revolting masses. As a result, the peasants from the surrounding area were admitted to the town for negotiations at the end of April under pressure from the Aschaffenburg citizenry. This led to violent riots, in the course of which the collegiate clergy’s houses were ransacked and members of the clergy were attacked and abused.

Governor Wilhelm now saw no other way out than to give in to the demands of the peasants gathered in the town. A little later, he signed the document known as the "Amorbach Declaration", a treaty that joined the nine towns belonging to the Oberstift to the Neckartal-Odewald cluster, as well as the peasants’ "12 Articles".

In the battle of Königshofen on 2 June 1525, the peasant armies united with the Neunstädtbund alliance’s contingents were crushed by the Swabian League troops. What followed was a great and horrible judgement for everyone involved, in the course of which the towns lost all their freedoms and privileges. The citizenry had to promise not to attempt to overthrow the those in power in the future. The town of Aschaffenburg was also fined 1,300 guilders.

By enacting the so-called Albertine Order, Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545, archbishop from 1514) introduced an early absolutist regime. The immediate consequences included the dissolution of the Neunstädtebund alliance, the installation of the vidame as the sole representative of the town lord, the abolition of the mayors’ offices, the loss of the guild freedoms and confiscation of the Strietwald forest. The continuous development of the town over the past centuries was thus abruptly slowed down and set back in large areas. As a result, Aschaffenburg largely sank into economic and political insignificance until the beginning of the 19th century.

After the end of the war, the Mainz Cathedral Chapter invited representatives of the Aschaffenburg collegiate church to discuss reparations for the damage inflicted during the Peasants’ War. This letter of invitation as well as the concept of a response from the collegiate church are preserved in copy in the Liber V. camerae (fol. 16r-17v.) While the town had to accept severe curtailments in the area of its legal and administrative powers, the collegiate church had its old freedoms and privileges ratified on 4 November 1528.